Can COP30 deliver on climate promises?

MACRO MIRROR Fahmida Khatun [Source : The daily star, Nov 12, 2025]

Global attention has currently turned to Belém, one of the gateways to the Brazilian Amazon, where the climate community has gathered for the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP 30) under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Marking a decade since the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015, this conference carries heightened global expectations for real implementation, accountability, and delivery of promises, rather than simply negotiating new ambitions. Being held against the background of a tense geopolitical scenario and devastating climate events in vulnerable countries, the issues that dominate the 12-day-long COP30 agenda carry far-reaching implications for the people and the planet.

First, countries will negotiate on adaptation-related outcomes at COP30, including a set of indicators to assess progress towards the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), which was anchored in the Paris Agreement. The GGA was designed to guide the transition from the countries' National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) to concrete actions by enhancing the adaptive capacity and strengthening resilience to climate change. The progress on the GGA is to be tracked through 100 indicators.

However, the indicator framework and operational details of GGA remain unfinished as reliable data and knowledge gaps prevail in vulnerable countries, which require time to build up their statistical capacity. COP30 is expected to finalise the GGA progress tracking architecture.

The second issue is new national climate plans, such as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the Paris Agreement, which every country is required to submit every five years. Each new plan should show updated and stronger action than before, reflecting what the countries can do. NDCs for 2025 need to explain the countries' plan to tackle climate change up to 2035. Between November 2024 and November 10, 2025, 109 countries have submitted a 2035 NDC target, which will draw attention in Belém.

To note, the Emissions Gap Report 2025 of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), published just before COP30, warns that the world is still not doing enough to minimise climate change risk. Based on the current pledges from countries, global temperatures could rise by 2.3 to 2.5 degrees Celsius by the end of this century. This means the Earth's temperature will go past the safe limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels within the next ten years, worsening heatwaves, floods, and storms, according to scientists. The most important goal now is to bring the temperature back down as soon as possible. Failure at COP30 to ramp up ambition or agree on credible implementation will make it increasingly implausible to keep the temperature within the safe limit.

The third issue is the scaling up of climate finance for developing and low-income countries. Mobilising and delivering adequate funding for mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage, especially for vulnerable countries, is a critical task. The new collective quantified goal (NCQG), adopted at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, urged scaling up finance for developing countries to at least $1.3 trillion by 2035, with a mobilisation target of at least $300 billion annually. The task at Belém is to turn that collective ambition into concrete financial support. According to UNEP's Adaptation Gap Report 2025, the annual global requirement for adaptation to climate change-induced events such as sea level rise, extreme heat waves and storms will be about $310 billion. However, in 2023, developing countries received about $26 billion—two billion less than the amount they received in 2022 and 12 to 14 times less than what they currently need—in international funding to help them adapt to climate change.

Fourth, it is expected that forests, biodiversity and tropical conservation, central to climate survival, will be at the focus at Belém. Hosting COP30 gives a symbolic boost to forest and nature conservation, since the Amazon rainforest holds about 60 percent of the world's largest tropical forest. Mechanisms like the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), a proposed blended-finance fund to incentivise countries to protect tropical forests, are expected to be a flagship outcome, providing predictable long-term funds to conserve and restore tropical forests.

Fifth, countries are expected to decide a new plan called the Belém Action Mechanism for a Global Just Transition (BAM) at COP30. Such a plan should aim for a shift to a green economy in a fair way where people come first, so that climate action creates new jobs, provides training for workers, and helps communities adapt their economies as industries change. The just transition pathway is critically important for climate-vulnerable countries like Bangladesh. The transition towards green growth, including renewables, sustainable agriculture, coastal defences and blue-economy solutions in these countries, depends on access to finance, appropriate technology and just transition frameworks. The COP30 outcome should be based on country contexts, to ensure climate plans and investments protect the planet, while supporting workers and building stronger, more inclusive societies. Agriculture and food systems is also one of the COP30 action agendas, since agriculture and land use are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG).

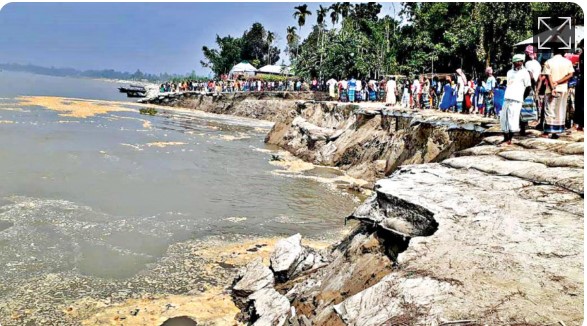

For developing and low-income countries, including highly climate-vulnerable ones like Bangladesh, COP30 is a strategic opportunity to expedite the implementation of various commitments. Bangladesh is on the frontline of sea-level rise, cyclones, river-erosion and climate-driven displacement. Therefore, obtaining clarity on adaptation finance and the GGA indicators is crucial. Implementation of global commitments on funding, technology transfer, capacity building and institutional strengthening is imperative for Bangladesh.

Moreover, the forest and nature agenda has implications for Bangladesh. Although Bangladesh does not have a vast forest cover like the host Brazil, the global forest agenda—which includes carbon credits, nature-based solutions and preserving critical ecosystems—affects the global carbon markets, international cooperation and South-South partnerships in which Bangladesh might engage.

Moreover, COP30 is being framed not only as a negotiation among states but as a session demanding all-of-society engagement, which includes governments, the private sector, indigenous peoples, civil society, and youth. This broader mobilisation is essential to scaling action and ensuring that agreements are not just signed but implemented with transparency.

If COP30 ends with weak commitments or compromised implementation pathways, the risks are profound, especially for climate-vulnerable countries like Bangladesh and for the broader global climate regime. It is not just about new promises; it is about cementing credible paths for the fulfilment of promises and ensuring vulnerable countries get a fair share of the burden and the benefits. A meaningful outcome from COP30 can unlock resources, technologies and partnerships essential for climate-resilient development in vulnerable countries. Conversely, the failure to make any progress will be a climate calamity.

Dr Fahmida Khatun is executive director at the Centre for Policy Dialogue.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries, and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.